During the Cold War, the Air Force Dropped an Unarmed Nuke on South Carolina

Amazingly, none of the Gregg family of Mars Bluff were seriously hurt, not even the cat

Considering how monumentally destructive nuclear bombs can be, one likes to think that their handlers are extremely careful when dealing with the powerful weapons. But, of course, mistakes sometimes happen. Just take the time in 1958, when a bomber accidentally dropped an unarmed nuclear warhead on the unsuspecting town of Mars Bluff, South Carolina. Over the years, the Mars Bluff bombing has faded from headlines, but the story recently got new life when a Freedom of Information Act request led to the government releasing previously unpublicized photographs taken during the Air Force’s investigation of the incident.

On March 11, 1958, a B-47 Stratojet bomber was cruising at around 15,000 feet in the sky above South Carolina. Its crew was just getting ready to begin their transatlantic trip from Hunter Air Force Base in Savannah, Georgia, to the United Kingdom as part of a mission called “Operation Snow Flurry.” The mission was essentially a drill so that bomber crews would be prepared for long missions in case of nuclear war – the bomber would fly from Georgia to Britain, where it would drop a bomb that would be retrieved by ground crews. However, this was during the height of the Cold War, and the planes were required to carry actual nuclear weapons in case the practice mission suddenly became real, according to Atlas Obscura.

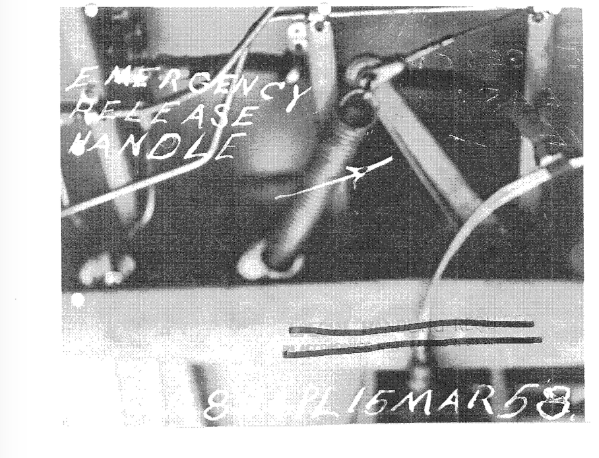

The mission started off normal, but very quickly it went off the rails. As the bomber passed over Mars Bluff, pilot Captain Earl E. Koehler noticed a warning light indicating their payload – a 4-ton Mark 6 nuclear bomb – wasn’t properly secured. As the pilot didn’t want a nuclear warhead rattling around in his plane, he sent his navigator, Bruce M. Kulka, to secure the weapon, JPat Brown writes for MuckRock. But when Kulka tried to lock the bomb back into place, he reached out to grab something to steady himself – and grabbed the bomb’s emergency release. The bomb fell, hit the bay doors, and plummeted towards Mars Bluff below.

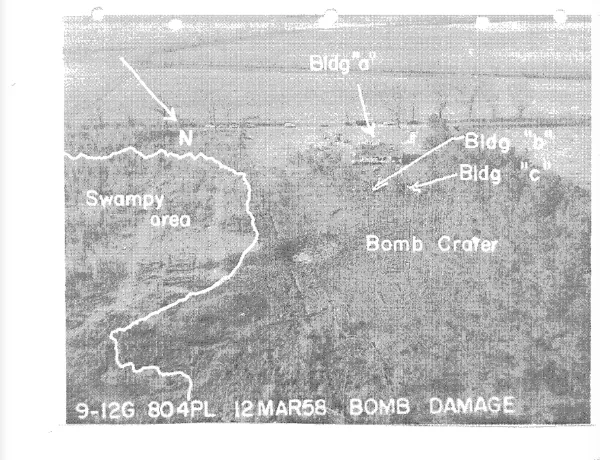

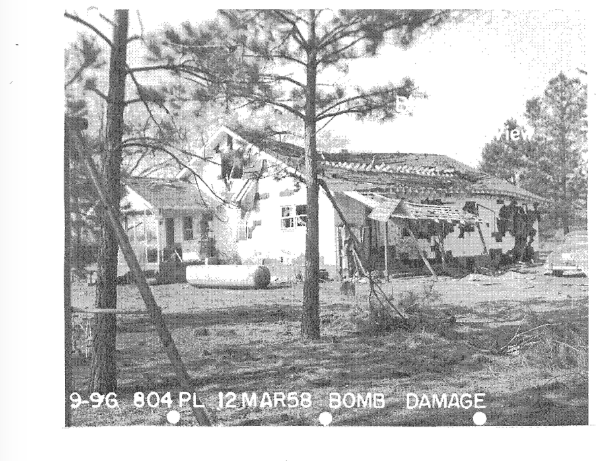

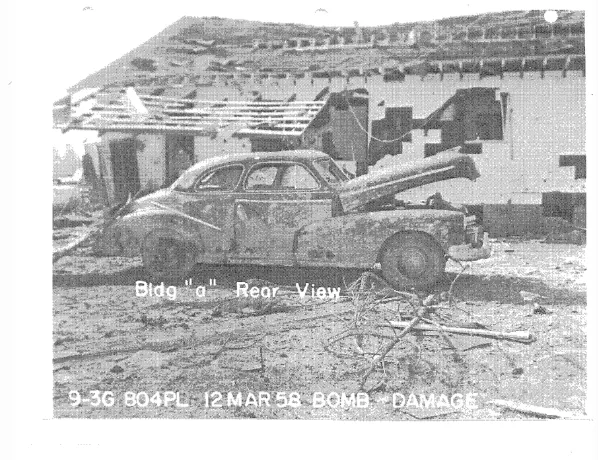

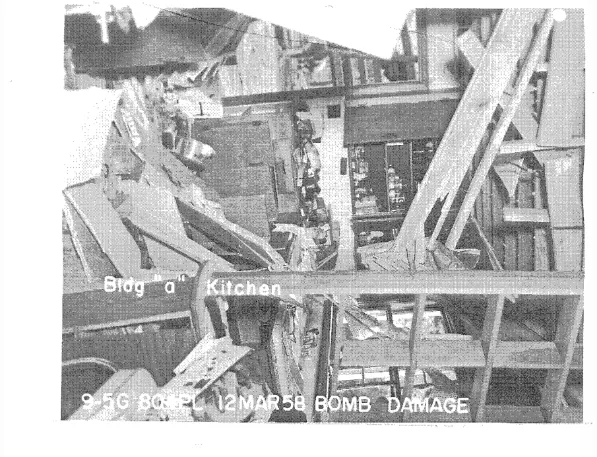

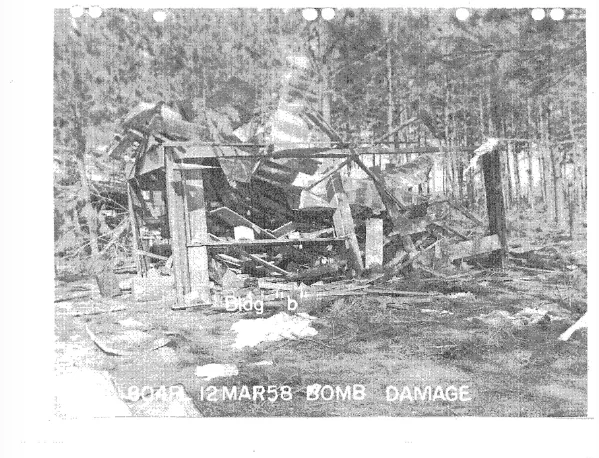

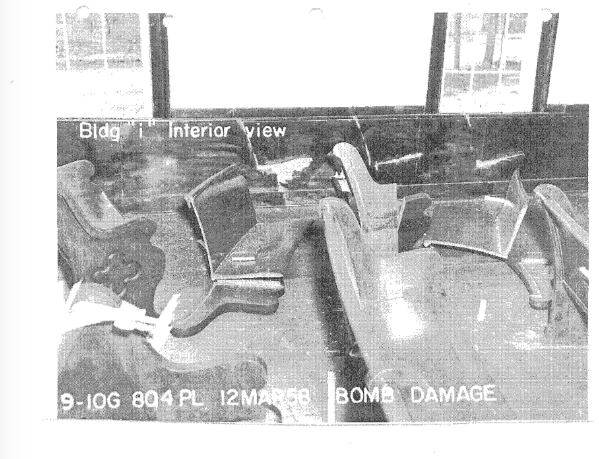

Luckily for everyone involved, the bomb’s nuclear payload wasn’t armed – its core had been removed for the duration of the flight, sparing the South Carolina town from bearing the full brunt of a nuclear blast. However, it was still loaded with the conventional explosives used to trigger the nuclear reaction. When the bomb landed, about 100 yards away from the home of the Gregg family, the force of the explosion tore through their house, Atlas Obscura writes.

“It just came like a bolt of lightning," Walter Gregg, Sr. said in the documentary Nuclear 911, SCNow.com reported. "Boom! And it was all over. The concussion …caved the roof in.”

Amazingly, none of the Greggs were seriously injured by the blast. The worst injury suffered by a family member was a gash on head of the mother, Ethel Mae Helms Gregg. Her husband, their three children, and even their pet kitten all survived. They were certainly shaken, but only sustained minor injuries, Brown writes. The only deaths caused by the bomb were a couple of nearby chickens. The Greggs’ house, however, was torn to shreds, and a nearby church was damaged as well.

The accidental bombing was widely covered in the international press at the time, and the Air Force formally apologized to the Greggs. The family later sued the Air Force for damages caused by the blast and ended settling for $54,000 (about $450,000 today), Brown writes. Today, the crater is marked by a plaque – luckily simply a marker of a quirky historical moment and not a massive tragedy.