The Arizona town of Eloy used to live off cotton until it sucked up so much groundwater the desert floor began to crack and collapse. The town withered and almost died. Then it found a new source of revenue: people, colour-coded in blue, green and khaki uniforms.

America’s biggest private prison operator built a complex with four prisons in Eloy and imported prisoners from across the United States. CoreCivic, previously the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), is now Eloy’s biggest employer and taxpayer, contributing about $2m to its $12m general fund budget.

In addition to generating property and sales tax revenues, the approximately 6,500 prisoners boost state disbursements by swelling Eloy’s official population to more than 17,000. “It’s a positive thing for a small rural community, a great help to us,” said Harvey Krauss, the city manager.

Under Donald Trump that bounty is set to grow: he wants to funnel more immigrant detainees to private prisons.

There is, in theory, a dilemma for this dusty town tucked between Phoenix and Tucson. One of the four prisons inside CoreCivic’s complex has been dubbed America’s deadliest immigrant detention centre. There have been 15 deaths, including at least five suicides, since 2003, according to an Arizona Republic tally.

A recent joint study by Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement (Civic) found that detainees who are incarcerated pending deportation proceedings were needlessly suffering and dying at Eloy and other facilities because of improper medical care and misuse of solitary confinement. It cited “systemic failure”.

Jose de Jesus Deniz Sahagun, 31, from Mexico, died after a disturbing suicide. Manuel Cota-Domingo, 34, a Guatemalan with diabetes and pneumonia, died when staff dithered over calling 911.

The Department of Homeland Security’s office of civil rights and civil liberties sent a report to Congress in 2015 complaining that the 1,520-bed facility ignored and delayed implementing its recommendations, including for better suicide prevention.

“They just give you water,” Miguel Cornejo, 40, who spent nine months there in 2015, told the Guardian. “If you’ve a headache, drink water. Stomachache, drink water. Cancer, drink water. Water is their cure for everything.”

Immigrant rights activists have protested outside the prison, which is surrounded by desolate scrub. Juanes and John Legend gave a concert there last year to highlight conditions.

Such notoriety could present a challenge to the residents of Eloy. It does not.

“It’s pretty much out of sight, out of mind,” said Krauss. Residents are spread over a 100 sq miles and many never see, let alone visit, the prison complex. “People just live their daily lives, do their own thing. Prison is just an industry.”

Mark Benner, a chamber of commerce spokesman, agreed: “We are non-political. If someone comes down here and protests they’re entitled to have their point of view. We’re interested in businesses.”

Residents echoed that view. Few were aware of the immigration prison’s controversial reputation. When told, they shrugged.

“If they’re in there, they’re there for a reason,” said Tony Pedigo, 39, a steel worker relaxing in the Tumbleweed bar. He had not heard of the suicides but saw no reason to fret. “Either they’re weak and snuffing themselves out, or it’s a way of covering up gang crime stuff.”

Rob Harness, 64, an electrician, had heard of protests but was not sympathetic. “The protestors ought to be shot. They’re just looking for trouble.” He also advocated a lethal policy for border crossers. “You come here a third time, we put you in the ground.”

Eloy is majority Latino. Many of the town’s undocumented residents fear going out lest they be nabbed and deported, said Cesar Diaz, 43, who runs a taco cafe with a Mexican flag. Lunch traffic has fallen about 60% since Trump’s inauguration, he said.

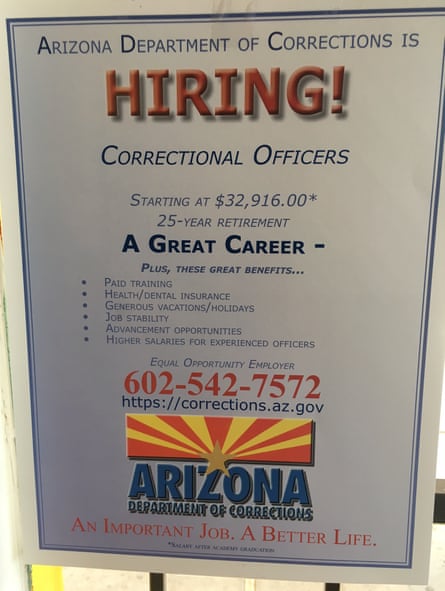

Yet there appears to be no resentment toward the guards, many Latino, who jail those who are caught. A department of corrections recruitment poster (“Hiring! An important job. A better life”) adorned the cafe wall. “Before we had the fields. Now we have the prison. It’s good pay,” said Diaz, 43.

Support here for the prison, a vital cog in deportation machinery, contrasts with anger at rallies across the US where activists protest Trump’s immigration crackdown.

For Eloy, earning a living comes first. Average per capita income is just $9,000. Poverty is rife. Almost nine out of 10 schoolchildren qualify for food aid.

Lack of economic opportunity “enslaves” residents, said Father Alonzo Garcia, a Catholic priest. “To get into the middle class, [working at the] prison is the best bet.”

The post office’s sole jobs flyer was for correctional officer positions: $31,885 starting salary, health and life insurance, paid holidays and sick days, bereavement leave, training programmes.

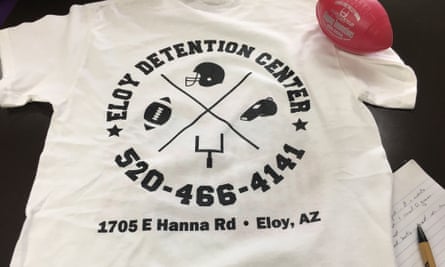

CoreCivic is active in the community, sponsoring food drives, marathons and school donations. Cheerleaders toss T-shirts with “Eloy Detention Center” logos into the crowd during football games, said Orlenda Roberts, superintendent of Santa Cruz Valley Union high school district.

“There are very few jobs so when you have a large institute in the middle of a small town it just takes on a life of its own,” said Juanita Molina, head of the Border Action Network advocacy group. “There’s a feeling of loyalty, either you’re with the company or you’re with the protestors.”

Isabel Garcia, a Tucson-based lawyer with the rights group Coalicion de Derechos Humanos, said economic hardship eroded solidarity. “When you have colonised people you have people who want to be like the coloniser.”

CCA opened its Eloy complex in 1994, during Bill Clinton’s presidency. Allegations about sub-standard medical care multiplied under Barack Obama, dubbed by some the “deporter-in-chief” for his administration’s record number of removals.

“The Democrats helped to create this massive incarceration and enforcement machinery and handed it over to Trump,” said Garcia. Border crossings have fallen but the spike in arrests in the US interior will swell detention numbers, she predicted.

Late in his presidency Obama decided to phase out the use of private prisons to hold federal prisoners. Hillary Clinton vowed to end the private prison system altogether. The day after Trump won CoreCivic’s stock jumped 43%. Trump subsequently signed an executive order to expand immigrant detention facilities and let private contractors build and run them.

CoreCivic referred queries for this article to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice), the government agency with oversight. A spokesperson said Ice officers made daily visits and inspections: “Ice officers and staff are committed to ensuring a safe environment for all those in the agency’s custody.” CoreCivic’s website says the Eloy detention centre offers education, vocational programs, drug rehabilitation and behaviour services. Photos show smiling, avuncular staff.

Cornejo, the former prisoner, who is now an activist with the rights group Puente, gave a darker view, alleging that guards were aggressive and made detainees feel like criminals. “It’s a place of sadness that should not exist.”

The Guardian was allowed to observe hearings at one of the immigration courts inside the facility: a spartan, compact room with whitewashed walls, fluorescent lighting, a calendar, a clock and a US flag. A black-robed judge, Linda Spencer-Walters, sat at a raised desk.

Eleven detainees waited their turn on wooden benches. A few spoke English and had lawyers. Most did not and relied on a translator and the judge to explain what was happening. Each hearing lasted on average eight minutes and set new dates for further hearings, evidence of a backlogged system.

Karen, a young woman from Guatemala, had requested asylum. The judge gave her a trial date: 23 April 2018, at 1pm. “That’s when I’ll hear all the details of why you can’t go back to Guatemala.”

Karen looked at the clock, then the calendar. She seemed to be calculating the days and hours. She looked numb. A guard ushered her out.